General Notes on Greek Folk Dances

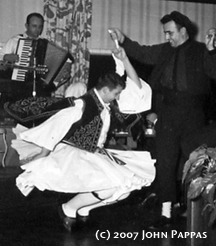

John dancing the Tsamiko to the music of John Kaplanis

at the El Cid in San Francisco, 1960.

My book, Ethnic Dances of Greece, will be coming out soon. If you are interested in buying an interim brief edition, or individual dance descriptions, I have ordering information and a sample available here. Below, I've included an abbreviated version of the introduction to my book, to give you a bit of background on the rich diversity of Greek folk dance.

Ethnic Greek Dances: An Introduction

Some Background and Occasions for Dancing

by John Pappayiorgas Pappas

Dancing has always been important to the Hellenic (Greek) people. In ancient times, dance, song, and music were all integral parts of the theater. In fact, the Greek word 'XOPOC', (HOROS), referred to both dance and song. The English words chorus, chorale, choir, and choreography all come from this same Greek word. Furthermore, there are numerous references to dancing in ancient literature. In the myth of Theseus, for example, Theseus and the Athenian youths dance the Yeranos, or Crane dance. In the Iliad of Homer, the youths depicted on a shield dance what seems to be a dance similar to the Syrtos in handhold and movements.

Furthermore he wrought a green, like that which Daedalus once made in Cnossus for lovely Ariadne. Hereon there danced youths and maidens whom all would woo, with their hands on one another's wrists. ... sometimes they would dance deftly in a ring with merry twinkling feet..., and sometimes they would go all in line with one another... There was a bard also to sing to them and play his lyre, while two tumblers went about performing in the midst of them when the man struck up with his tune. (Homer. The Iliad. book xviii.)

Archaic era vase showing Greek line dancers.

Besides several references in various sources from the ancient and Byzantine world, there are drawings, paintings, and small statues which depict dancers and musicians. Invariably, the dancers are in a circle or line, often with a musician or musicians in the center. The dancers are joined with the same common handholds still used in our Greek folk dances today. These include the shoulder hold, the chain hold, and the most common joining of hands (shoulder height with elbows down, like a 'W').

Prearchaic dance circle, 9th c. BC. Olympia.

5th-3rd c. BC circle of dancers, with avlos player inside.

Today, Greeks dance for many reasons. For example, they use dance as a means of celebrating, as a form of self expression, and also as a part of ritualistic drama. In effect, dance is just as important to the Greeks of today as it was in ancient times. First, dancing is a part of the celebration of the important occasions in the lives of the Greek people; it is an important part of weddings, baptisms, name day (Saint's day) celebrations, and all religious holidays. Dancing also occurs spontaneously at taverns or in homes, often even without musicians. All that is needed is singing and fellowship. If the mood is right, dancing and singing will take place. The celebration is an expression of the joy of the moment. Dance is also a form of self expression. The dancer can "create a dance" by mixing various step variants with the basic step of a dance to make something new or different at that moment. This improvisation by individuals is an exciting part of Greek dance. In fact, each time the Greeks dance, the dance is different in some way from the way it was done before, or from the way it may be done in the future. These differences are not great; they are subtle and are the result of the self expression of the individuals as they dance. The dancers can express joy, heroism, sadness, grace, strength, pride, anger, rejection, sensuousness, humor, and almost any other emotion through dance. In Greek literature for instance, Zorba, in Zorba the Greek by Nikos Kazantzakis, must dance when his joy or sorrow are overwhelming. Just as in the ancient Greek drama, the emotions are purged or expressed through the catharsis of the dance and music. We can see such emotions expressed in a sad, heavy Zeibekikos, the happy, exuberant Syrtos, or the heroic, masculine Tsamikos or Beratis.

Men Dancing in Epiros. Drawing by Pavla Pappayiorga; 1971.

Dance also plays a part in ritualistic drama for the Greeks. The ritual use of dance can be seen in the traditional Byzantine form of the Greek wedding as it is still performed in the Greek Orthodox wedding ceremony. The bride and groom, the priest, and the koubaros perform a procession circling around a table three times to the song "Isaia Horeve." This ritual procession is supposed to represent a dance, and it is done in an open circle moving counter-clockwise, just as the majority of the Greek dances are danced. It follows the crowning of the couple with the stefana, or flowered crowns, and it marks their first movement as a couple (androgyno) in their new married state. Here, the word "horeve," which means dance, also means rejoice as a synonym for "dance and sing."

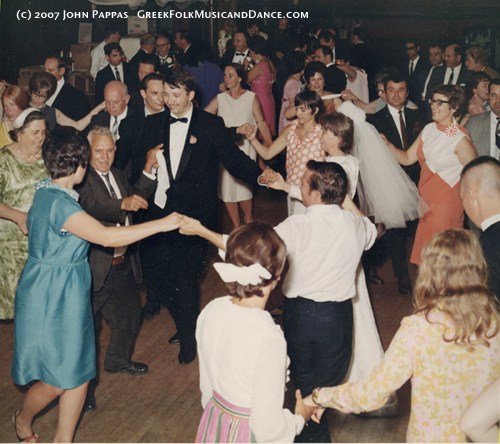

Tsamikos: John's and Paula's wedding, 1968. Leading the line is John's great-uncle, Thodoris Pappayiorgas.

There are also other uses of dances as parts of rituals. The various dances which are used as bride's dances (Horos Tis Nyfis), Greek Thracian fire walkers' dances (Anastenaria), and for other uses are usually dances from the basic village repertoire which are used ritualistically on that occasion, sometimes to a special song. For instance, one of the national or pan-Hellenic dances such as the Syrtos can be used as a wedding dance (Horos Tou Gamou), a bride's dance (Tis Nyfis), or for many other purposes. Thus, Greek dances are also used ritualistically for those "rites of passage" which mark important occasions in the lives of the Greek people.

In Zevgolateio: Stavros Belesiotis and John Pappas dancing Tsamikos, 1966. Apostolis Stamelos on klarino.

San Joaquin Delta College Hellenic Dancers doing Syrtos at the school's new campus dedication in 1977. John is playing a Thracian gaida.

Greek dancing in Foustanelles (men) and Florina costume (ladies). 1970s.

John plays Klarino while his brother Jim, cousin Annette, and wife Paula dance Syrtos. Kandyla, 2006.

Dancers from the island of Amourgos, Smithsonian Bicentennial Folklife Festival, 1976.

Dancers from the island of Amourgos, Smithsonian Bicentennial Folklife Festival, 1976.

Cretan dancers doing Kritikos Syrtos, Smithsonian Bicentennial Folklife Festival, 1976.

Skyrian Ballos, Smithsonian Bicentennial Folklife Festival, 1976.

This page was last updated on 10/7/2007.